This case study was published by Amanda North, founder of Artisan Connect, on April 25, 2017. Read the original piece on LinkedIn.

"Three years ago I founded an impact venture providing market access for global artisans to help them thrive. I'm sharing this case study hoping it may be helpful to others supporting the artisan sector and social ventures more broadly."

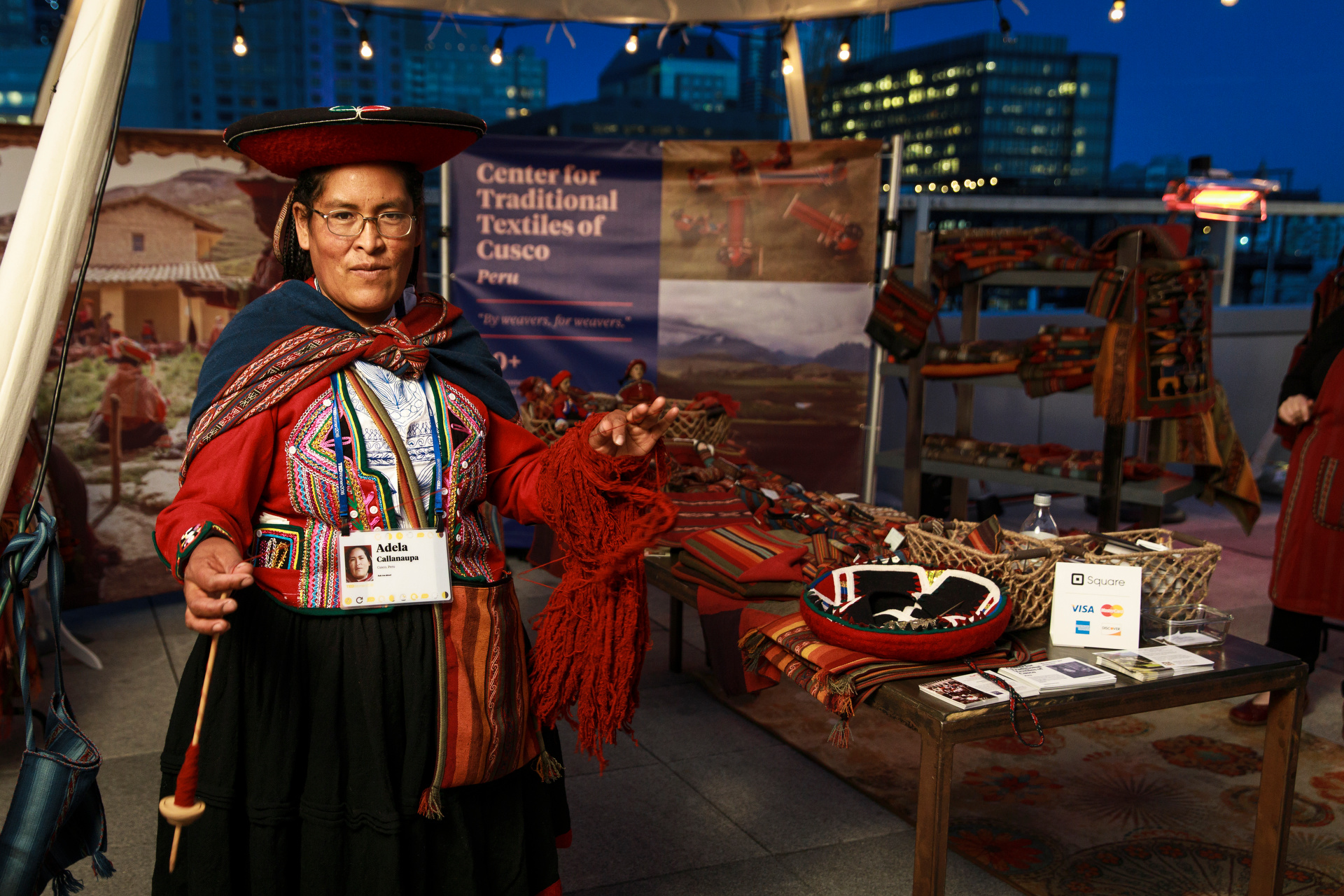

Problem Statement: Each year millions of people in the developing world leave their villages in hopes of better income opportunities. The cities lack infrastructure to support this swelling population. Women are particularly aversely affected, falling into trafficking and other horrific outcomes. At the same time, cultural traditions are being lost due to this mass migration. But the villages do contain important potential sources of income, including crafts. Although some artisan groups have received capacity building support, their key issue is identifying and reaching consumers who will properly value their products. They do not want handouts or donations—the artisans want ongoing revenue streams and entrepreneurial opportunities for the next generation.

Founder’s Background: I served for over thirty years in executive marketing roles for technology companies. Then I was injured in the Boston Marathon bombing, April 15 2013, which catalyzed me to pursue my passions and purpose. I founded Artisan Connect in July 2013, initially supported as an Entrepreneur in Residence through Santa Clara University’s Miller Center where I had served as a volunteer mentor. To this venture, I brought my background in strategic partnering, brand building and marketing with fast growth organizations.

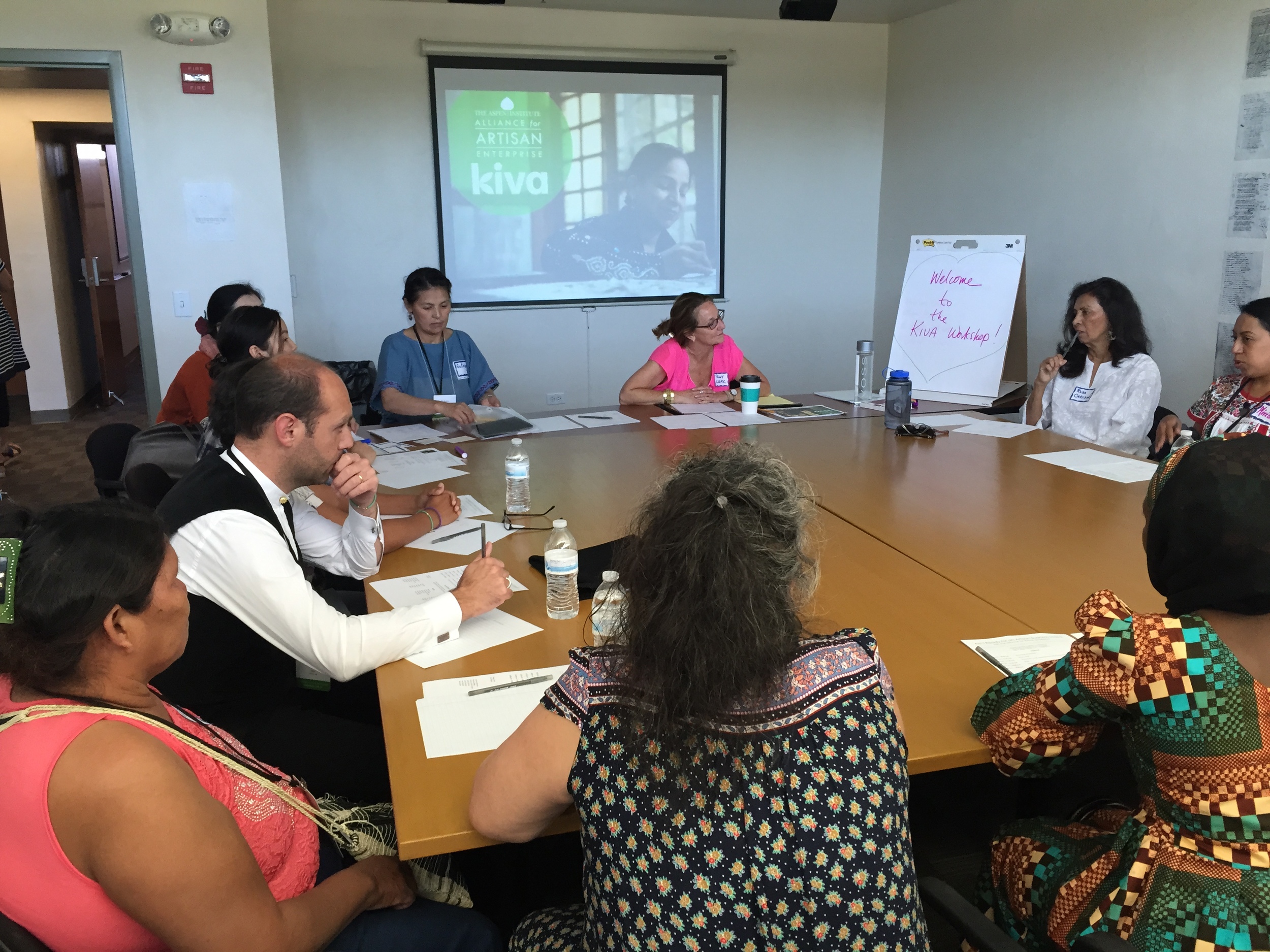

Concept: I had observed through my volunteer work at the Miller Center that the artisan sector has focused on capacity building and not enough on market connection and that the sector is fragmented, preventing scaling. With Artisan Connect, I sought to build a common platform to support artisan groups around the world, enabling their own brand stories to be showcased, but providing the ease of purchase required by US customers.

Business Structure: Counsel advised me to structure Artisan Connect as a C Corporation, incorporated in Delaware. From the outset, we were mission driven and moved aggressively to B Corp certification, which we gained in August 2014. Our articles of incorporation contained reference to our social mission.

Organization: My initial team comprised volunteers and contractors, to minimize spend and buy time to ascertain what roles were required for this kind of business. SCU supported me with three students who worked with me during the Fall of 2013 to research and develop the business plan. An externship funded by Bain & Company enabled a recent Stanford GSB graduate to work with us for six months.

Leadership team: One of my greatest challenges was that I was unable to identify a business partner with complementary skills to my own. Twice I hired people very experienced in retail but they were not a good fit for the start-up world. Another challenge was that I never had a formal board of directors—I was holding off until we raised our first institutional round of funding. My seed investors, though supportive, were generally hands-off.

Funding: Having developed the high-level concept for Artisan Connect, in the Fall of 2013 I approached longtime friends/colleagues for seed funding. I closed $250,000 in convertible debt by the end of 2013 enabling us to commence operations in January 2014. In total I raised $1,350,000 in convertible debt.

Business Model: Artisan Connect acted as an intermediary between artisan groups and consumers. I decided not to work with individual artisans because generally they don’t have the quality control, unit quantities, shipping abilities or business front end that are provided by artisan collectives and other social impact groups serving artisans. We purchased product from the artisan groups at prices they determined. We required transparency on how the payment is split between artisan wages, social services and administrative costs. Artisan Connect’s retail prices reflected 1/3 to these groups, 1/3 to shipping costs, 1/3 to Artisan Connect.

Channels: We chose eCommerce as our principal channel for its scalability. But we found that this platform alone is not ideal for artisan-based businesses for the following reasons:

- Generally, prices/margins are driven lower online than in person

- eCommerce customers expect deep discounts, free shipping and robust customer service

- They are comparison shoppers—Artisan Connect products were compared with look-alike products from large retailers, mass produced

- It is hard to communicate authenticity, quality and “story” online

- Social media built followers, but did not translate to sales

Based on these insights, we evolved our model to multichannel, using in person events to engage customers, then remarketing to them through weekly emails. This succeeded in slowly building a loyal customer base

Marketing: Driving people to our website was more challenging than we anticipated given the congestion in the eCommerce space. This spurred us to promote our products through other online channels that already had built a base of relevant customers. We experienced an increase in sales but our margins suffered significantly, and this strategy did not enable us to build our brand. A more successful strategy was our co-marketing with affiliated groups, such as Global Fund for Women, that share our core mission.

Target customers: our original target was millenials because we believed they would resonate with our social impact mission. However, they do not appear to be spending significant money on our class of product (home décor and gifts) though they are purchasing other social impact sectors such as consumables (food and body care/cosmetics). Our principal customers turned out to be women 40-60, often purchasing for their millennial offspring or friends

Growth: By the end of 2015 Artisan Connect was partnering with 30 artisan groups in 16 countries across the developing world. Five of these organizations were our lead partners in terms of sales. We built a database of 2,000 active supporters including 500 customers, many of whom had purchased multiple times. Our average transaction size was $175. We had a team of four full time staff plus an outsourced bookkeeper and graphics designer. Occasionally, we used an outside web developer. We had a six- member advisory board.

We closed 2015 at $125,000 in revenues which was far lower than original projections due to low site visitor/sales conversion rates. Because of our small order quantities, shipping costs still amounted to 30% of our COGS, which significantly reduced our margins, preventing us from being able to sell wholesale. Recognizing that revenues were not increasing at the pace we had anticipated, we brought down our burn rate to extend our runway.

Business Model Evolution: Working capital was a huge expense in our initial model because we purchased product directly from artisans. They required the entire purchase order to be paid upfront so they could buy materials to produce the orders for us. There was a long lead time before we could start generating revenues from the products: 6-8 weeks for product production, 2-3 weeks for shipment to the US via air, then another week for loading information onto our website and promoting the products.

Recognizing this significant working capital expense and inventory risk, we decided to partner primarily with artisan groups who are drop shippers (they already have their products warehoused in the US). Instead of being a retailer, we became a true marketplace, offering these artisans 70% of the retail price—a better margin than they had previously received, while Artisan Connect took a commission of 30% for our marketing and ecommerce support. They were responsible for shipping to the end customers.

Challenges with Additional Funding: During the first half of 2015 I spoke with over 40 individuals and institutions about providing follow-on funding, but with no success. Scale was our biggest issue—several of the organizations liked our mission but only would invest once we had reached a $1 Million annual run rate. Many other social impact investors did not understand the importance of our role as an intermediary. Their charter was to provide funding directly to needy people in-country. In addition, many funders focus on specific geographic areas, such as sub-Saharan Africa or India, so our reach across the developing world was not a fit.

Strategic Alternatives for Growth: By the Fall of 2015 it was apparent we would not secure next round (institutional) funding. I refocused on trying to land a significant strategic partner/acquirer where Artisan Connect could be a semi-autonomous group, tapping into the parent company’s customer base, funding and infrastructure. We had productive conversations with a number of successful online marketplaces but ultimately they decided we were too small to be worth the effort. I also pursued some out-of-the-box ideas, like pitching an artisan TV series (where viewers could buy the products online) and approaching the Olympics about doing artisan showcases/shops.

A Belly Landing: In January, 2016 I informed my investors that, although we still had money in the bank, we were not able to carry the company forward. I found new jobs for our employees, liquidated inventory, transferred our office lease to another B Corp, shut down our warehouse, and put our eCommerce website on hold. By May, 2016 the company effectively had shut down.

I was reluctant to dissolve the company, especially since we were making progress against our social impact objectives, although not at the pace to continue operations. I decided instead to merge the company with a non-profit organization in New York that also focuses on supporting global artisans. At the end of 2016, my investors converted their notes to stock and donated the shares to this non-profit entity, enabling them to write off their investments in Artisan Connect.

Lessons Learned: I managed Artisan Connect through a graceful wind down, with no outstanding liabilities or obligations. My investors were supportive and say “they would back me again.” From my conversations with peers in the industry, it appears we’ve all faced similar issues. Scale is certainly one of the problems—there are too many competing companies splitting investment funds and customers. The artisan sector would be better served with a consolidated platform—which is what I had set out to do with Artisan Connect…

If I could start Artisan Connect today, here are some things I’d do differently:

- Organize initially as a non-profit and convert to for profit when at scale

- Aggregate the sector so we could pool customers, achieve discounted shipping rates, improve margins

- Focus on B2B and use this revenue stream to build the consumer brand

- Provide in person as well as online engagement through pop up stores

- Identify a business partner from the outset to complement my skillsets

- Engage more active support—through a formal board

Through my experience founding and leading Artisan Connect, I have become committed to the social impact sector, broadly defined. I am inspired by the people I’ve interacted with, and the mission-driven spirit of collaboration. I believe strongly in “business for good” but now recognize that the sector is at a much earlier stage than I had thought, in terms of investment capital and infrastructure. Wherever my next steps lead, I hope I can contribute to moving the sector forward.

Do you have a case study or other lessons learned from running an artisan enterprise? Let us know! Please email info@allianceartisan.org with your content.